Warning: Undefined variable $num in

/home/shroutdo/public_html/courses/wp-content/plugins/single-categories/single_categories.php on line

126

Warning: Undefined variable $posts_num in

/home/shroutdo/public_html/courses/wp-content/plugins/single-categories/single_categories.php on line

127

In the wake of disaster, often our attempts at conceptualization provide valuable insight as to our values or belief systems. In the cases like Pernin’s work on the Peshtigo fire, access to one man’s beliefs, in this case Catholicism and God’s divine will, can be found in his attempt to understand his experiences. The Chicago fire, however, presents a unique opportunity to access the nation’s belief system due to the volume of explanatory work that grew out of the city’s newspapers, correspondence, writing from various other great cities across the nation, etc. Due to the sheer magnitude of individuals concerned with what transpired in Chicago and the volume of explanatory work available, we are able to do a case study of the nation’s maxims. Carl Smith’s, “Faith and Doubt” is an in-depth review of the two distinct ways that Chicagoans and others attempted to explain the significance of the Chicago fire. What becomes clear upon examination is that both these explanations are the result of the intersection between three crucial elements of American society: religion, class, and American exceptionalism.

The first method of explanation that Carl Smith describes in his piece is the view of Chicago rising from the ashes like a phoenix as a moral pillar that was chosen by God to uplift the nation. This explanation asserts that the Chicago was essentially baptized by the fire, and that only the most pure, most pious, most humble, and most hardworking of the population remains. It also asserts that God hand-picked Chicago to be this uplifting example, and that only Chicago could have emerged triumphant from a trial such as this. Also, this explanation posits that through her misfortune the rest of the United States could return to its philanthropic and giving core. Essentially this version explains the fire as a gift and declares Chicago’s future bright as ever.

This explanation is essentially an intersection of religious fervor and a strong belief in American exceptionalism. This explanation provides evidence that the country is still very much a religious nation, looking to the Bible and God’s divine will as explanation for misfortune. Their belief that Chicago was hand-selected and uniquely prepared to emerge triumphant from this kind of disaster – which is why God chose Chicago rather than say London – is indicative of this belief in American exceptionalism.

The second method of explanation that Carl Smith describes in his piece is the view of Chicago sinking into fiery peril. There is talk of God’s punishment being exacted upon the city, and a focus on the crime that runs rampant in the wake of the fire. They describe the fire as an act of Satan which was designed to plunge the city into ruin. There is the juxtaposition of “good” wealthy or middle-class Chicagoans suffering at the hands of vagabonds who are now free to enter the city to take advantage of its vulnerability. And furthermore, there is the characterization of the lower-class Chicagoans taking over parts of the city where they were previously not welcome as a result of their own deplorable way of life.

This explanation, like the previous one, utilizes religion to explain the significance of the Chicago fire. In this case, God is exacting his judgment against the city, and therefore it should be taken as a warning to change their way of life. It is even characterized as an attack of the Devil. The emphasis on the good majority of Chicagoans – wealthy and middle-class inhabitants – being taken advantage of by vagabonds – lower-class inhabitants – is indicative of class stratification. Catherine Schmidt talks about the element of class that comes into play in reference to the Chicago fire. The tension between the classes, with the wealthy dismissing the poor as dirty, conniving, responsible for their plight, and ready to steal from those who worked hard for their success, is very clear here. The tensions that arise along with industrialization and the urbanization that occurred as a result play out here.

Therefore, it is clear that the United States, at the time of the Chicago fire, was still a very religious minded country, that believed in American exceptionalism, and struggled with the intensification of class stratification that is born of the industrial revolution. Often what we learn from eyewitness accounts, and primary sources such as newspaper articles or pieces of art, is what those who created them were thinking. We learn about their fears, belief systems, hopes, and aspirations. And by tapping into a large enough body of these sources, we can almost take the ideological temperature of the nation.

Contrary to what the title might suggest, I will not be talking about deep dish pizza. I will, however, discuss Carl Smith’s well-written article, “Faith and Doubt,” and the importance of the Chicago fire. Rarely do I ever enjoy reading (I picked the wrong major), but Smith’s analysis of the fire’s social affect on the city whetted my appetite for something different than descriptions of the fire’s physical destruction. One of his arguments claims that, at least among fire literature and Chicagoans, the city’s importance grew following the fire. He claims “the destruction indicated not the degree of Chicago’s venality or misfortune, but the grandeur of its destiny.” (130) The Chicago fire became the city’s “epic moment” that spawned a belief that Chicago was “pure, heroic, and modern.” (131) Religious explanations for the fire further contributed to this thinking by claiming “God smote the city…as a warning and a lesson for all other cities.” (135) Therefore, members of the city and nation must protect the valuable future of Chicago (by protecting the social order) because only Chicagoans could withstand such a divine beating. I viewed these religious justifications as comparable with the struggles of Job in the Bible. Smith cites individuals that believed the deaths as a result of the fire were deserved due to a lack of “character and resolve.” (150)

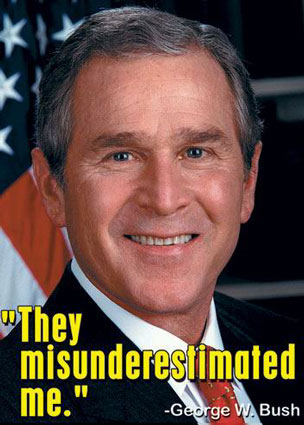

Contrary to what the title might suggest, I will not be talking about deep dish pizza. I will, however, discuss Carl Smith’s well-written article, “Faith and Doubt,” and the importance of the Chicago fire. Rarely do I ever enjoy reading (I picked the wrong major), but Smith’s analysis of the fire’s social affect on the city whetted my appetite for something different than descriptions of the fire’s physical destruction. One of his arguments claims that, at least among fire literature and Chicagoans, the city’s importance grew following the fire. He claims “the destruction indicated not the degree of Chicago’s venality or misfortune, but the grandeur of its destiny.” (130) The Chicago fire became the city’s “epic moment” that spawned a belief that Chicago was “pure, heroic, and modern.” (131) Religious explanations for the fire further contributed to this thinking by claiming “God smote the city…as a warning and a lesson for all other cities.” (135) Therefore, members of the city and nation must protect the valuable future of Chicago (by protecting the social order) because only Chicagoans could withstand such a divine beating. I viewed these religious justifications as comparable with the struggles of Job in the Bible. Smith cites individuals that believed the deaths as a result of the fire were deserved due to a lack of “character and resolve.” (150) to the extent these petty differences were forgotten, I thought back to 9/11 and how unified America was. Following 9/11, President Bush’s approval rating was through the roof; proof that disaster causes those affected to forget other predicaments. In the wise words of my Davidson advisor, “when shit hits the fan, people rally around their own.”

to the extent these petty differences were forgotten, I thought back to 9/11 and how unified America was. Following 9/11, President Bush’s approval rating was through the roof; proof that disaster causes those affected to forget other predicaments. In the wise words of my Davidson advisor, “when shit hits the fan, people rally around their own.”